Below is the research that we conducted in our writing of the "The Kane Shadow: Murder is a Circus". Delavan is chock-full of interesting history and stories. Scroll through to find out about...

From the Delavan Wisconsin Historical Society

Delavan sits in the middle of what was at one time an inland sea. During the Ice Age, many glaciers, the last of which was known as the Michigan tongue, covered this area. The Michigan tongue descended down what is now known as Lake Michigan. A large section of this glacier broke off, pushing southwest into the area now known as Walworth County. Geologists have called this section of the glacier “the Delavan lobe”.

The first humans known to inhabit the Delavan area were Native Americans around the era of 1000BC. Later, between 500-1000 AD, Mound Builders lived in what is now the Delavan Lake area. Mound Builders were of the Woodland culture. The effigy mounds they erected along the shores of Delavan Lake numbered well over 200, according to an archeological survey done in the late 1800’s by Beloit College. Many were along the north shore of the lake where Lake Lawn Resort now stands. The Potawotomi Indians also settled around the lake in the late 18th century, although there were only an estimated 240 in the county. Some of their burial mounds are preserved in what is now Assembly Park.

From the mid 17th century through the mid 18th century, this area was known as “New France” and was under the French flag. It came under British rule and a part of the Province of Quebec following the French-Indian War. In accordance with the Treaty of 1783 it was turned over to the United States and a part of the newly established Northwest Territory.

Between the years of 1800 and 1836 the Delavan area was part of the Indiana Territory, followed by the Illinois Territory, finally becoming part of the Wisconsin Territory in 1836. Statehood was granted in 1848.

Delavan’s first white settlers arrived in 1836, finding the area to be dense forests with prairies on both the east and west sides with plenty of game available for hunting.

Lakes and streams surrounded the area. The first known settler in the Delavan area was a man from the Rockford, Illinois area named Allen Perkins. Arriving in the spring of that year, he built a log cabin for his family at the base of the hill along what is now Walworth Ave.

That same summer, two brothers from New York arrived in Chicago with the intention of starting a temperance colony. Samuel and Henry Phoenix were hoping to form a settlement “pledged to temperance, sobriety and religion; and where should a poor, despised colored man chance to set his foot, he might do it in safety” according to the writings in Samuel’s journal. They traveled north of Chicago in search of the most desirable spot to settle. After traveling around this area and finding nothing to their liking, Henry returned to New York and Samuel continued the search. Samuel discovered what is now the Delavan area after spending a night in an abandoned Potawotomi wigwam. He later met Perkins and Perkins two brothers-in-law as they were traveling the same route to Spring Prairie to get provisions. They all returned to Delavan the next day. Samuel Phoenix stayed with the Perkins family until his provisions arrived from Racine.

Phoenix was a successful businessman in New York and staked many claims in the Delavan settlement. It wasn’t long before he and the Perkins family were at odds over the naming of the colony. The Perkins had filed for the settlement to be named “Wilksbarre”, but the postmaster who received the request and was to have forwarded it to Washington for approval was a friend of Phoenix and returned it instead.

Phoenix was joined in Delavan by relatives and they soon outnumbered the Perkins clan. Phoenix then filed the name of Delavan with the Belmont Legislature. Born in 1793, E. C. Delavan, whose surname the city now bears, was a temperance leader in New York State. He never saw the town that carries his name. He died in 1871. Phoenix also filed the name of Walworth County, taking the name from Chancellor Rueben Walworth, past president of the New York Temperance League.

Perkins eventually moved from Delavan and Phoenix then took over his claims. Before long, Phoenix held claims on most of the area. The settlement was touted as a great temperance colony to those in New England and many came west to settle here. Most new settlers were successful farmers, good businessmen and financially secure. The majority of them traveled here via steamers on the Great Lakes and came west from their landing in Racine by wagon. Most stayed with Phoenix until their own cabins were built. He had also established the first general store in town. Land sold for $1.35 an acre and was primarily used for agriculture. Wheat crops were the most predominate and brought a good cash flow to the farmers.

The Baptist church, organized in 1839 was the first church in the newly formed town. From this church grew the first anti-slavery and temperance societies in Wisconsin. The belief in temperance was so strong that it was included in all deeds that no alcohol could be bought or consumed on the premises. This unconstitutional inclusion was outlawed in 1845.

Samuel and Henry Phoenix completed construction of the town’s first gristmill in 1839, at the current Mill Pond site. It could grind 100 barrels of wheat per day and was the main business in Delavan for the remainder of that century. The owners had rights to build a dam and control the water levels and the power used at the mill.

Most of the settlers were from New England and were not tolerant of the Europeans that tried to settle in the area. Many travelers were turned away from the inn, operated by Israel Stowell. Now the oldest building in Delavan, it still stands at the SW corner of Walworth Ave. and Main St.

The Phoenix brothers died within two years of each other. Samuel in 1840 from tuberculosis and Henry in 1842. Both are buried in Old Settler’s Cemetery, located in the 300 block of McDowell Street. About 6 months after Henry’s death, the first town meeting was held at Israel Stowell’s. William Bartlett, a half brother of Samuel and Henry was elected chairman. It is said that he did not possess their leadership qualities.

1845 brought the end of temperance in Delavan. In 1847, Edmund and Jeremiah Mabie, proprietors of the U.S. Olympic Circus – then the largest traveling show in America – chose Delavan for their winter quarters, a year before Wisconsin attained statehood and 24 years before the Ringling Brothers raised their first tents in Baraboo, Wisconsin.

The Mabie brothers chose Delavan due to its ability to support the circus horses and other animals. These animals were the most important assets to the 19th century circus, both for transportation and performance. Delavan’s abundant pastures and pure water provided everything the Mabies required. The Mabie Circus stayed at the present site of Lake Lawn Resort on Delavan Lake, where it created a circus dynasty that survived in Wisconsin for the next 100 years.

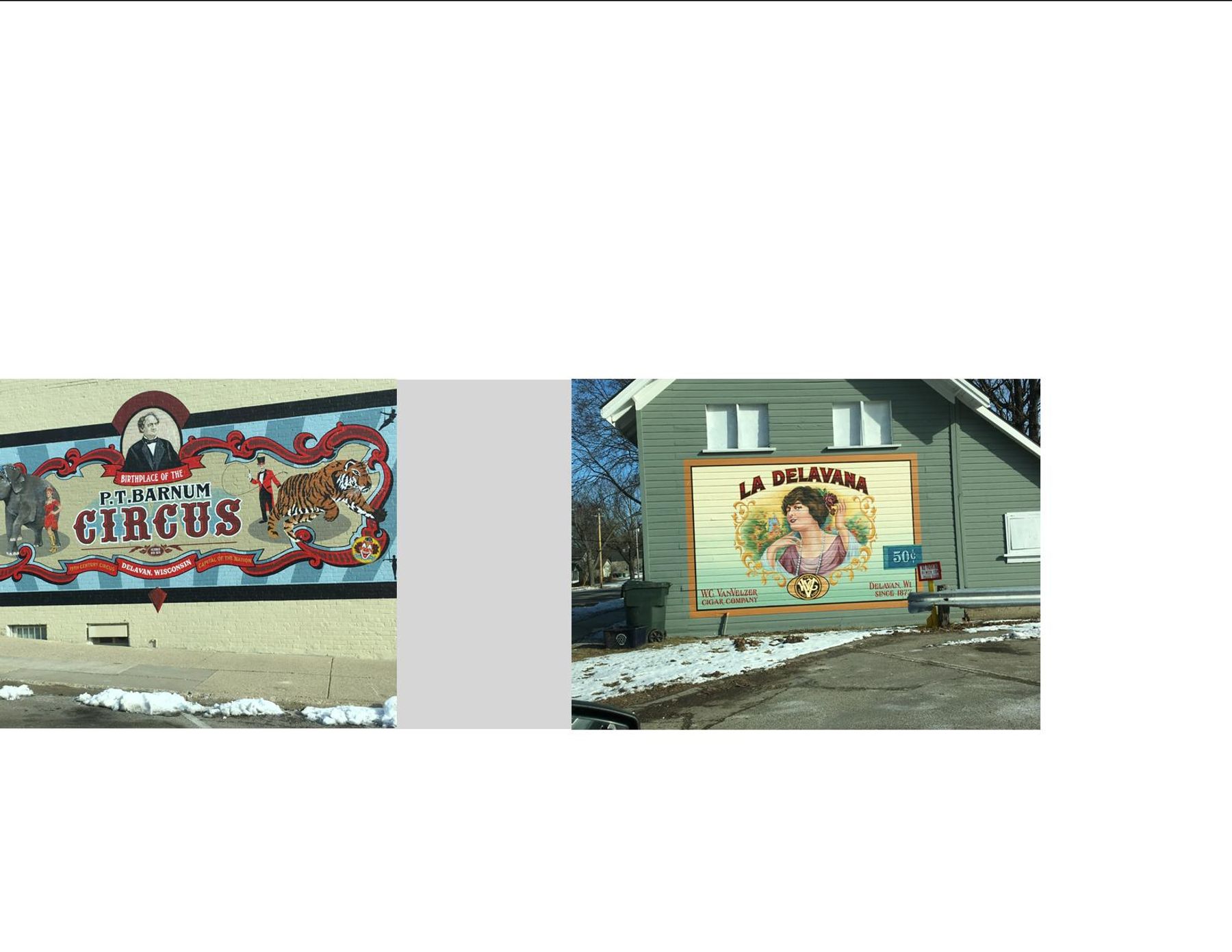

As time passed, the circuses grew in strength and numbers; hundreds of clowns and circus performers from over 26 circuses set up their winter quarters in Delavan from 1847 to 1894. The P.T. Barnum Circus, “The Greatest Show On Earth,” was founded in Delavan in 1871.

But, as times changed so too did the circus era in Delavan. It came to an end in 1894 when the E.G. Holland Railroad Circus folded its tents. Except for a handful of local performers, who continued the tradition, the circus vanished from the community. Within a generation, the familiar ring barns and circus landmarks were gone. On May 2, 1966, the U.S. Postal Service selected Delavan to issue the five-cent American Circus Commemorative Postage Stamp. Today, more than 150 members of the old Circus Colony are buried in Spring Grove and St. Andrew’s cemeteries.

The Mabie brothers took over where the Phoenix brothers had left off. They were financially well off and soon owned over 1,000 acres in the township. The purchased the Phoenix brothers gristmill, orchestrated the original plank road that was laid from Racine to Delavan and saw to the completion of the Racine-Mississippi railroad to this point in 1856. Edmund served a term as village president and they were both extremely fundamental in the development of Delavan during the pre-Civil War era.

In the late 1840s, many new immigrants came to Delavan, but were not welcomed by the Baptist element already established here. Many of the new arrivals were Irish and Catholic and settled in the Darien area. In 1856, many more Irish laborers arrived with the construction of the railroad and settled here.

The Wisconsin School for the Deaf was founded on April 19, 1852. It is situated high on a hill, overlooking Delavan, on land donated to the state for it’s sole use by Franklin Phoenix. Phoenix was a friend and neighbor to the Ebenezer Chesebro family whose daughter Ariadna was deaf. Chesebro had employed Wealthy Hawes to teach his daughter in 1850. Hawes himself was hard of hearing and had attended the New York Institute for the Deaf and Dumb. As Delavan’s population grew, so did the increase in the deaf population. By 1852 Hawes successor, John A. Mills was teaching eight area children and the need for state assistance became apparent. The Chesebros, along with some help from friends and neighbors petitioned the state for a school, the land was donated and the school was opened.

In 1861 the first manufacturing plant was built in Delavan. Founded by Trumball D. Thomas, it manufactured windmills and wooden pumps. It employed 35 men. Over the years it grew and evolved and included a foundry and machine shop.

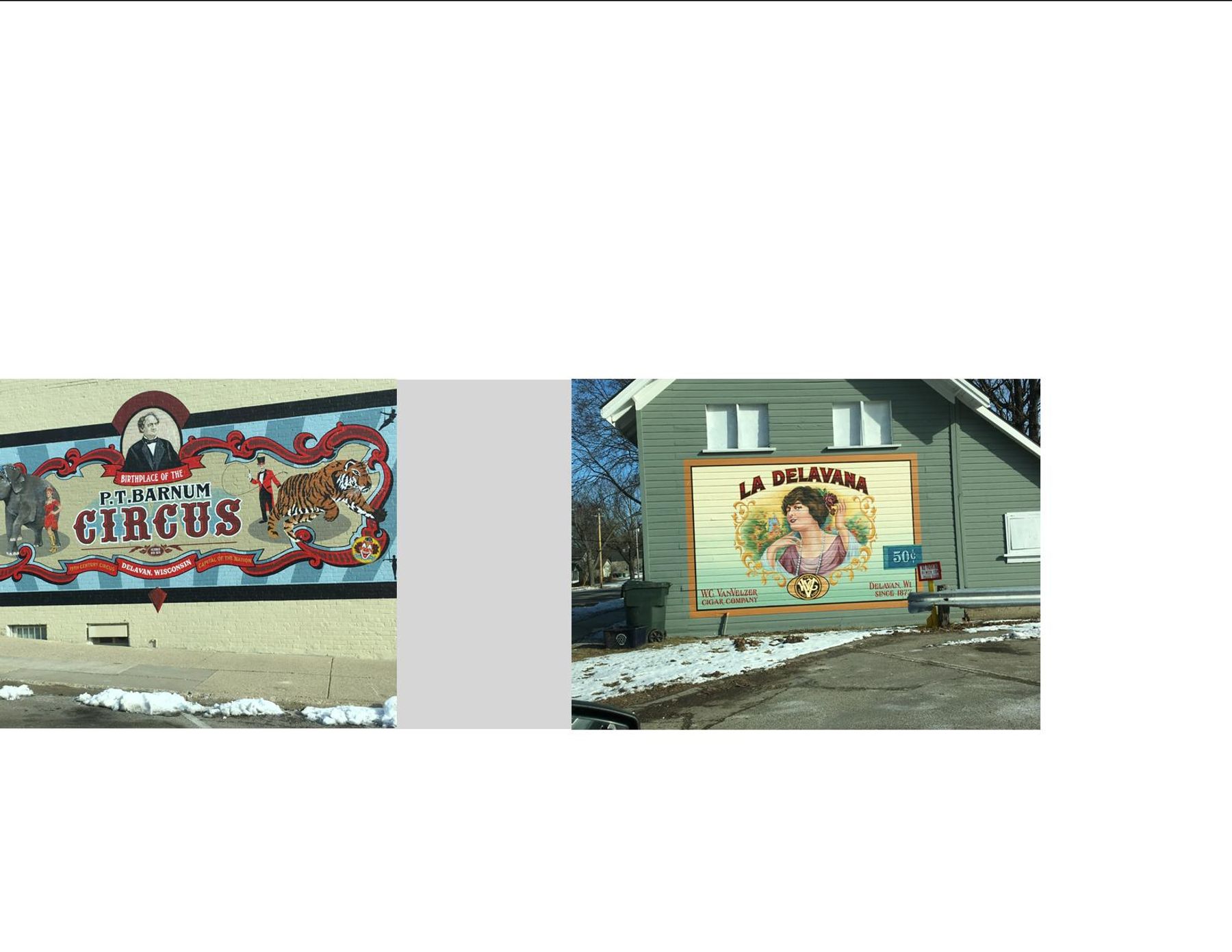

64 Delavanites perished in the Civil War, more than all other wars combined. Following the Civil War, many manufacturers built in Delavan, including the Logan cheese factory, the VanVelzer cigar factory, the Jackson tack factory and the N. W. Hoag grain elevator.

Development at Delavan Lake didn’t begin until the first permanent residence was built by Dr. Fredrick L. VonSuessmilch in 1875 along the north shore. Mamie Mabie opened a small hotel at Lake Lawn three years later. A steamboat launch was built at that location also. The next 20 years saw a building boom of private houses, hotels and resorts. Most of the residents were summer retreats for Chicagoans who came up on the train, which at that time stopped here 6 times a day during the summer months. Livery buses took people from the train station in town to the resorts around the lake.

Many changes came to Delavan in the last decade of the 19th century. Fires devastated the business district in both 1892 and 1893. A new school was built in 1894. Electricity was first brought to town in 1896. Delavan became a city in 1897.

During the early 1900s, Delavan became a recognized art center. The Chicago Art Institute held summer classes here for 15 years. Famous artists that had studios here include William T. Thorne, Adolph and Ada Schulz, Frank Dudley and Frank Phoenix.

The Bradley Knitting Company was established in 1904. The first major manufacturer in town, it employed up to 1,200 people over the next 30 years. Delavan saw a rapid growth in building after Bradley opened. The average new home during that period cost $1,800.

The first paved street in Delavan was Walworth Avenue between Terrace and Fourth streets in 1913. Bricks were laid at a cost of $1.79 per square yard. Sidewalks soon replaced the boards that had previously been used to walk on. In 1915, a 3 block boulevard was built between Fourth and Seventh streets on Walworth Ave. The brick streets still remain, although they were redone in the late 1990s. The boulevards still remain an attractive sight on the main street through town.

During this same time period, Aram Public Library, the Delavan Post Office and streetlights were added to the downtown area. Horse and buggies gave way to automobiles and plumbing went from outdoors to indoors. Dairy farming took over as the leading agricultural income and milk was transported to Chicago by train.

Delavan lost 16 servicemen during World War I. Influenza during that same time claimed the lives of many at home.

Delavan’s strong economy helped to see it through the Great Depression, keeping it a bit less devastating than it was for many areas of the country. The resorts and ballrooms around the lake were instrumental in keeping the economy alive. Slot machines were abundant in the ballrooms and were known to have caused a few gang warfare incidents.

As the Depression wore on, Bradley Knitting Company fell into hard times. A Chicagoan by the name of George W. Borg came in and loaned the business some capital. He also opened a small manufacturing plant that made clocks for automobiles. Borg was also largely responsible for the development of the automobile clutch. Around this same time, William C. Heath developed Sta-Rite Products that manufactured water systems. Heath later designed landing gears for B-17 and B-29 bombers and also developed a high-speed submersible pump that was used in the capture of a German submarine. In 1940, Thomas B. Gibbs started a factory that manufactured timing and electrical devices. During World War II, Borg and Gibbs completed over 30 contracts for the U.S. government. Because of the number of government contracts, Delavan was listed as one of the top ten prime targets for enemy sabotage.

Delavan was immediately affected by the bombing of Pearl Harbor when Walter Boviall, a DHS graduate, went down with the Arizona. Twenty-three Delavan servicemen lost their lives in this war. Government contracts kept Delavan’s economy healthy during this time.

The late 1940’s and early 1950’s brought a building and baby boom to Delavan once again. The Korean War took the lives of three Delavanites. Progress brought a new water tower, which is still in use in Tower Park. Borg Industries and Ajay Industries joined the industrial firms of Delavan. The Mill Pond was dredged during this time and began to be used for swimming in the summer and ice-skating in the winter. It still serves the purpose today. The new Delavan-Darien High School was built and the first senior class to graduate from it was the class of 1958.

The 1960s brought the assassination of President Kennedy, who had stopped in Delavan during his presidential campaign. George Borg, son of George W. Borg was elected to the State Senate. A D-DHS graduate, Gary Burghoff launched his acting career in the role of Radar O’Reilly in the movie “M*A*S*H” followed by the TV Series. The Viet Nam War took the lives of six area servicemen. Local attorney, Ernst John Watts became Walworth County Circuit Judge. Delavan was chosen as the First Day Cover city for the issuance of a five-cent commemorative American Circus postage stamp. The Lange Memorial Arboretum was opened and a large section of the north shore of Lake Comus was donated to the city by Ben Dibble for use as a wildlife and botanical refuge.

The seventies through the nineties brought more growth both in industry and residential aspects. Joining the businesses in Delavan were Swiss Tech and Andes Candies. Highway 15 was expanded to a four lane interstate highway and became I-43, running from Beloit to Milwaukee. Delavan’s first female mayor was elected in 1976. Beth Supernaw had previously served on the common council, representing the second ward. Fires devastated the city during this decade. In 1978-79, The Colonial Hotel, the American Legion and the Ajay South Second Street buildings were all destroyed by fires.

Since then, Delavan has become the home of Waukesha Cherry-Burrell, Stock Lumber, Bergamot Brass and other industrial companies. Ajay closed is doors in the 1990s. Geneva Lakes Kennel Club brought Greyhound racing to the lakes area. Two shopping centers built in the late 1980s on the east side of town added many shopping alternatives to area residents. A few additional have been built along Hwy. 50 since then.

From http://www.assemblypark.com/

-☛ 1840's - The Mabies purchased Assembly Park in 1847 & later their heirs sold to the Delavan Lake Assembly Association.

-☛ 1890's - Delavan Lake Assembly Association in 1898. was formed by a group of Delavan business men.

-☛ 1900's - Delavan Lake Assembly Association in 1898. was formed, after the land was purchased from the Mabie heirs.

-☛ 1910's - Assembly Park was noted for its annual Chautauqua type programs featuring nationally known lectures

-☛ 1920's - Assembly Park's first fire house 1920's

-☛ 1930's - 8 cottages burned down, new new park benches, a new concrete boat ramp, new concrete curbs were all added.

-☛ 1940's - The first Arbor Day was held, "My Brother's Place" was opened.

-☛ 1950's - Gail Reece, the caretaker at the park, the Children's Thursday Night Dances started.

-☛ 1960's - Seventy Ladies from Assembly Park, traveled to the Playboy Club, as part of the Arbor Day celebration.

-☛ 1970's - Construction of the Delavan Lake Sanitary District began as well as the construction of Route 15 , now Router 43.

-☛ 1980's - The lake Level was dropped to save the lake. Rob Mohr was hired as Caretaker of the Park.

-☛ 1990's - 100 years anniversary, water system was turned off, new playground equipment and new park benches were installed.

-☛ 2000's - Assembly Park.com was created, the beach Wall was painted.

-☛ 2010's - The new roads were approved and installed.

Delavan Assembly Park Auditorium (above), faced the lake, was described as a round building with wooden benches and a sawdust floor.

Assembly Park's first fire house, photo taken in 1920's.

Charlie Flint - Boats for Rent, both power and not power boats.

Gail Reece

1950's Early - The Thursday Night Dance - was started.

July 16, 1964 from the Delavan Enterprise

Rob Mohr, Caretaker of the Park

In Circus history, it's not only the human performers who are remembered. Certain animal acts are also remebered in the fondest of terms. In the case of Indian elephants, Romeo and Juliet, both are remembered, but only one of them is remembered fondly.

Romeo stood 19 1/2 feet tall and weighed 10,500 lbs. He also had a nasty habit of killing his keepers.

By the time he died, in the summer of 1872, Romeo was responsible for the deaths of five people, and at least 25 horses. He also nearly tore apart a theater in Chicago, and terrorized the cites of Delavan & Lake Geneva when he had escaped from his pen, one winter day.

By contrast, Juliet, was a gentle giant. A charming animal, who was loved by her trainers, and people all over the country.

Originally from the area that is now known as Sri-Lanka, Juliet came to America in 1851, to work in P.T. Barnum's Asiatic Caravan.

It was during the 1850's, that Juliet was paired up with Romeo, and the two would perform a musical act. Romeo would turn the crank on a hand organ, while Juliet would dance.

In February of 1864, Juliet died at the Circus' winter camp, along the northern banks of Lake Delavan (where Lake Lawn Resort is today). With the ground frozen solid, it was ordered that Juliet's body be dragged out to the frozen lake, and left. Then once the lake melted, the body would, and did sink to the bottom. It is said, that it was Romeo who was forced to drag Juliet's body across the frozen lake (the Circus would later use this experience as the reason why Romeo turned mean, and to garner sympathy, to prevent him from being exterminated after each of his attacks).

Some say it wasn't Juliet's death that turned Romeo mean, but the death of another elephant, by the name of Canada (whether this was before or after Juliet's death, is unknown by this author).

Canada died when she fell through the floor of a train car as it traveled over a bridge in Iowa.

Before Canada fell, it was Romeo that held onto her for over an hour. When it became apparent that Canada could not be saved, and for fear of losing both elephants, trainers forced Romeo to let go of his hold on Canada. Canada fell. Severly injuring herself, she had to be exterminated.

It is believed by some, that this was the moment Romeo turned bitter, violent, and most of all,

hold a grudge.

Over the next few years, Romeo became impossible to control. His rampages became folly for the newspapers, who reported on every death, and every violent outbreak. At one point getting so bad, that on February 25, 1872, the New York Times told it's readers, that "Romeo has outlived his usefulness."

On June 7th, 1872, Romeo died in Chicago, from an infected foot. Upon death, his body was removed from the Circus grounds, and taken to the public dump, where it was left to rot.

Today, the only reminder that Romeo ever existed, is the statue of him that sits on the corner of

E. Walworth Ave. and N. 2nd St., in Delavan. But if there was an elephant mean enough to return from the great beyond, it's Romeo.

From the Walworth County Today

DELAVAN—There was a time in Delavan when it wasn't unusual to see elephants lumbering down Walworth Avenue or drinking from Lake Comus, or watch zebra grazing in pastures near High and Parish streets.

Exotic sights were common when more than 20 circuses called Delavan their winter home in the mid-to late 19th century.

Historical accounts trace Delavan's earliest circus connections back to brothers Edmund and Jeremiah Mabie, who raised horses on their New York farm. Many of the Mabies' neighbors were circus performers, and in 1840, the brothers jumped on the circus band wagon themselves, creating a tent show.

In four short years, the Grand Olympic Arena and United States Circus had grown to 27 wagons and 150 horses. By 1847, decades before P.T. Barnum or the Ringling Brothers, the Mabies had the largest traveling circus in America.

That year, en route to Janesville from a performance in Milwaukee, the Mabies stopped their circus wagons in Delavan to rest and—according to one newspaper account—hunt prairie chickens. Impressed by the area's verdant woods, plentiful streams and prairies, the brothers decided they'd found the perfect spot to house their show during the winter months when they weren't on the road.

They set up the first permanent winter headquarters in the Midwest, purchasing 400 acres and two barns for a little over $3,000. The land was most of what is now Lake Lawn Resort, adjacent to Assembly Park and Inlet Oaks.

“It all started with the Mabies, who were looking in what then was 'the wild west' at that time to try to find someplace that was similar to their New York home in vegetation and water access,” said Patti Marsicano, Delavan Historical Society president and the author of two books on Delavan.

Delavan had it all: lots of timber for heating fuel and building materials, ample water and enough grazing and farmland to raise crops for their horses and a menagerie of animals, including hungry elephants that could eat 200 pounds of hay a day.

Delavan also had something else essential for traveling circuses—a great location. It offered easy access to multiple regions and the advantage of getting out at the start of the season ahead of Eastern-based shows, said Peter Shrake, archivist at the Circus World Museum in Baraboo.

Before railroad became common transportation for circuses, the shows drove their circus wagons from town to town, state to state. The Mabies played Wisconsin, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and South Dakota, the East Coast, and southern states like Missouri, Arkansas and Texas. For one short season, they even traveled by boat, playing port cities around the Great Lakes.

Word of Delavan as the Mabies' winter quarters got around, and by 1858, four different shows followed suit. Delavan-based circuses multiplied. The Mabie name was associated with two other circuses here. Some Mabie circus performers and employees left to start their own shows, like the Holland family of riders, acrobats and owners who settled in Delavan. In 1858 they formed the Holland & McMahon Circus, which performed for Union troops during the Civil War and became forerunner of USO entertainment shows.

Delavan resident and dentist George Morrison was a circus promoter who did dental work on the road with his show. One newspaper account said Morrison “extracted teeth from (a) circus wagon with no anesthesia, but sounds of the band probably drown out any moans.”

Of the more than 100 circuses that started in Wisconsin, Delavan was home to a reported 28—more than any other city in the state, including Baraboo, which had only nine. Not all of the circuses were as large as the Mabies' show, but most needed a place to spend the winter.

“The primary mission of a circus winter quarters was to refurbish the show in the off season,” Shrake said. “A traveling circus encountered considerable wear and tear over the many months on the road. The winter months allowed for the repair of worn out and creation of new wardrobe and equipment—props, wagons, tents. New acts were developed in the off season as well.

“Concerning animals, generally speaking, usually the horse stock—specifically the horses used to pull the various wagons—were kept at local farms for the winter. The exotic animals and ring-performing horses were usually kept near the winter quarters in heated buildings.”

A Milwaukee Sentinel article on local circuses noted, “Their winter home resembled a small village with the animal quarters, repair shops, training quarters and other buildings. With the coming of winter the showmen returned to Delavan and always had a large part in the life of the city.”

Both the Mabies had permanent homes in Delavan, including one on Fourth Street and Walworth Avenue. Other circus performers stayed at local boarding houses or hotels.

Delavan, settled by two other brothers from New York—Samuel and Henry Phoenix, who intended to start a temperance colony—wasn't initially welcoming of the Mabies and their ilk.

“Most churches opposed the circus, claiming it was an immoral presentation that took money out of the community,” wrote the late Delavan historian Gordon Yadon in a local newspaper article.

Delavan was dubbed “The Wickedest City in Wisconsin” because of its circus connections and the rough element that seemed to be a part of circus life.

“If you went back to the time when circuses traveled by wagons, they were followed by people trying to make money who hung out on the fringe of the circus,” Marsicano said. “Call them unsavory characters, snake oil salesmen, quick-change artists—the circuses drew those types of people.”

But the Mabies were different. Edmund Mabie joined the Delavan Congregational Church, was active in the community and became a civic leader, instrumental in getting projects like a 60-mile plank road built between Racine and Janesville. The brothers purchased the Delavan Milling Company and a saw mill in Janesville. Like other circus owners they were wealthy men and well-respected for their community involvement.

At the time Delavan had a population of less than 1,000 but it was growing, and city officials couldn't deny the circuses' impact on the local economy, from feed dealers and blacksmiths to mechanics and wagon makers.

Circus roustabouts and performers, from acrobats to clowns, became part of the area each winter.

So did the circus animals, including horses, elephants, camels, lions, leopards, zebra, snakes, even buffalo.

Albert the elephant, owned by the Holland-Gormley circus, was kept in a round house at 608-610 E. Walworth Ave. Purchased in 1889 from another circus in Philadelphia, Albert was sent by rail to Chicago, then—because there was no direct line to Delavan—to Clinton, where he was met by two circus workers who walked him to Delavan.

Albert was said to be gentle, although one account said when the circus traveled by railroad, and Albert was housed for the night in the animal car, he kept reaching into the widow of the adjoining car, where the workers slept, using his trunk to pull the blankets off their beds.

By 1864, the Mabies, then in poor health, sold their circus to Adam Forepaugh for $42,000. The animals and equipment were moved to Chicago a year later.

E.G. Holland's circus was the last circus organized in Delavan in 1892, and when that show called it quits in 1894, signs of the circus's imprint were disappearing.

“Within a generation of 1894, the familiar landmarks such as ring barn equipment were all gone,” Yadon wrote in a newspaper article.

A Milwaukee Sentinel article dated Nov. 13 1921 was already lamenting the fading circus history as it described a circular building on the LeBar farm near Delavan Lake. “The old building was at one time the 'ringhouse' where the riders trained and the acts rehearsed during the winter months…” the story said.

Some signs of Delavan's circus history are still there: a state historical marker on the west side of Tower Park on East Walworth Avenue, fiberglass statues of a giraffe, elephant and clown in the same park, even two downtown circus murals painted last year by the WallDogs.

There are also nearly 100 circus performers and owners buried in Spring Grove and St. Andrew's cemeteries. Marsicano said plans are in the works to replace the circus grave markers that were set in 1962.

Marsicano said few 19th-century Delavan circus photographs exist because residents then time found circuses so commonplace.

“The circuses were here all the time, and in our society, when you see something all the time, it's no big deal. People were blasé about it.”

Ironically, circuses also found Delavan a poor place to perform because attendance was generally low.

After all, local residents were already used to seeing elephants heading down Walworth Avenue.

Circus workers hoist the big top in 2003 at the former Geneva Lakes Kennel Club when the Carson and Barnes Circus made annual stops in Delavan. While the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey circus has announced it will close in May, circus heritage always will be ingrained in Wisconsin's history. P. T. Barnum founded his circus in Delavan. Terry Mayer/file photo

WALWORTH COUNTY SUNDAY -- The Big Top is coming down.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey, which called itself The Greatest Show on Earth, announced earlier this month it was closing in May, after rallying for years against a difficult economy, changing tastes in entertainment and pressure from animal rights groups.

When Ringling Brothers made a decision to retire its performing elephants two years ago because of protests, attendance dropped even lower than predicted, according to Feld Entertainment, which owns Ringling Brothers.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey’s final shows on May 21 in Uniondale, New York, have sold out, but online ticket exchanges are offering tickets at prices inflated by as much as 560 percent, with lower level ringside seats at The New Coliseum costing as much as $2,000, according to some websites.

Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey had a historically long run: 146 combined years for the shows. The fact that circuses like Ringling Brothers have such a history is testament to their success, said Peter Shrake, archivist at Circus World Museum in Baraboo.

“I think like any successful, long-running show, it comes down to good management, excellent performers and a willingness to be flexible,” Shrake wrote in an email. “A successful show knows its audience and gives that audience what it wants. Clearly for 146 years, the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Circus was able to do just that.”

Our circus heritage

The history of the traveling circus is about as long, and part of its storied past is linked to Wisconsin.

More than 100 circuses got their start in the state. Nine called Baraboo home, including the one formed by the brothers Ringling, who grew up there.

The site of their old winter quarters -- where they returned after each performing season to work on new acts and make repairs to wagons and equipment -- is now where the Circus World Museum stands.

But when it came to a real circus city, Wisconsin residents need look no further than Delavan, which in the 1800s was home to 28 circuses.

That’s when one of the most famous circus promoters, P.T. Barnum, organized his circus in 1871.

Barnum’s traveling circus underwent several incarnations until Barnum teamed up with James Bailey to create the Barnum and Bailey Circus.

Barnum’s circus is memorialized downtown in Tower Park where it is among three statues that commemorate the great traveling shows.

The statues include a giraffe named Ginny and Romeo the elephant, rearing up on its hind legs to a towering height of 20 feet.

The real-life Romeo, a 10,500-pound elephant owned by the Mabie Circus, had a reputation as a rogue and was connected to the death of five handlers.

Standing beneath Romeo is the 6-foot-tall statue of a clown who represents Lou Jacobs, a Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey performer whose famous face was plastered on magazine covers, posters and even a U.S. postage stamp.

By 1907, Barnum had sold his circus to Baraboo's Ringling Brothers, which ran them separately until finally merging in 1919 and forming the now famous Ringling Bros. and Barnum and Bailey Circus.

Before Barnum, Delavan’s earliest circus connections date back to brothers Edmund and Jeremiah Mabie, who raised horses on their New York farm. Many of the Mabies’ neighbors were circus performers, and in 1840, the brothers jumped on the circus bandwagon themselves, creating a tent show.

In four short years, the Grand Olympic Arena and United States Circus had grown to 27 wagons and 150 horses. By 1847, decades before P.T. Barnum or the Ringling Brothers, the Mabies had the largest traveling circus in America.

That year, en route to Janesville from a performance in Milwaukee, the Mabies stopped their circus wagons in Delavan to rest and -- according to one newspaper account -- hunt prairie chickens. Impressed by the area’s verdant woods, plentiful streams and prairies, the brothers decided they’d found the perfect spot to house their show during the winter months when they weren’t on the road.

They set up the first permanent winter headquarters in the Midwest, purchasing 400 acres and two barns for about $3,000. The land was most of what is now Lake Lawn Resort, adjacent to Assembly Park and Inlet Oaks.

Word of Delavan as the Mabies’ winter quarters got around, and by 1858, four different shows followed suit, finding Delavan’s central location and access to grazing land, water and timber a great asset. Delavan-based circuses multiplied.

Many of those circus owners and performers bought homes, got involved on civic boards and city projects and became neighbors, said Patti Marsicano, president of the Delavan Wisconsin Historical Society and author of two books on Delavan.

“The circus was part of the community,” Marsicano said. “The Mabie brothers invested financially in the area, purchased a mill.”

She said there are few photographs of circus life in Delavan because residents found sights like elephants walking down Walworth Avenue or zebras grazing near Lake Comus so common.

Circus people made an impact on the area in another way, spending money at grocery stores, hotels, blacksmith shops, wagon makers and feed stores.

“I think in those early days that was a good revenue source for Delavan,” said Walworth County historian Ginny Hall. “There were a number of former circus people who settled in Delavan and Darien and helped the economy of those communities.”

By the end of the 19th century, the physical imprint of the circus was disappearing from Delavan, but Hall finds traces of its presence decades later.

She pointed to Delavan’s Spring Grove Cemetery, where dozens of circus performers and workers are buried with colorful circus markers on their graves.

“I think it’s a source of pride that Delavan was considered a good spot for winter quarters,” Hall said. “When I came to the county in 1962, I still heard about the houses in Darien and Delavan where circus people had lived. And being that Delavan was the site where the circus stamp was initiated (in 1966) is a signal that the circus was still very important then.

“Today, all you have to do is go around to the circus mural (painted by the Walldogs in 2015) to see that circus history is still alive.”

Shrake sees the circus’s influence in today’s popular big-scale productions.

“Cirque du Soleil is a contemporary re-imagination of the circus. The Feld family, the owners of the Ringling show, are also producers of Disney on Ice,” Shrake said. “It is hard to imagine that the skills the Feld family developed while operating the circus did not in some way translate into their other entertainment endeavors.

“A number of notable movie stars, including Burt Lancaster, got their start in the circus,” he added.

And even without Ringling, Shrake believes smaller circuses will still continue to perform.

“The circus has always been a changing and evolving art form,” he said.

From the Wisconsin School for the Deaf website

In 1839, Ebenezer Chesebro moved his family from New York to the Delavan, Wisconsin area. The Chesebro family had a daughter, Ariadna, who was deaf and had attended the New York Institute for the Deaf and Dumb (NYI). In 1850 the Chesebros hired Wealthy Hawes to teach their daughter and a neighbor boy who was also deaf. Hawes, who lived nearby, was hard of hearing, and a graduate of the New York Institute.

Ariadna Chesebro is known as The Face That Launched WSD.

The Chesebros invited John A. Mills, also an NYI graduate, to take Hawe's place in 1851. With the area's increase in population, the school had grown to eight children and the Chesebros decided they could no longer afford to privately finance the education of their daughter and the other students.

In 1852, with the help of their friends and neighbors, they submitted a petition to the Wisconsin legislature requesting the establishment of a school for the deaf. Franklin K. Phoenix, a neighbor and close friend of the Chesebros, offered to donate to the state all the land necessary for the school. The governor signed the law appropriating funds for a school building, staff, and general operating expenses on April 19, 1852.

The Wisconsin School for the Deaf has been in continuous operation since its founding, and has operated since 1939 as a bureau of the state Department of Public Instruction. The school is a part of the state system of public education and as such has the same standards as those set forth by the Department of Public Instruction for all schools in Wisconsin. WSD also serves as a resource on deaf education for all Wisconsin school districts.